Adoption

Adult Adoptee Voices Are Changing Adoption Narrative

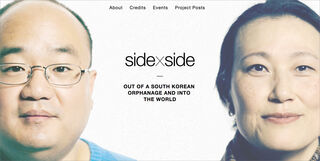

Guest post by Glenn Morey, director of the documentary project “Side by Side.”

Posted November 19, 2018 Reviewed by Devon Frye

I’m happy to present this guest blog by Glenn Morey, an award-winning documentary filmmaker. He was born in South Korea and adopted to the U.S. in 1960. He is half of a 35-year, husband/wife filmmaking team based in Denver.

I am neither a psychologist nor a scholar. I am a Korean-born, inter-country, transracial adoptee. And I am a filmmaker.

South Korea is the longest and largest case of inter-country adoption in history—more than 180,000 infants and children since the mid-‘50s, peaking in the ‘80s and ‘90s—setting the model for inter-country adoption as we know it today. Almost all were adopted transracially, and most of us are now adults.

Over the past five years, I produced and co-directed the documentary film project, “Side by Side: Out of a South Korean Orphanage and Into the World,” filmed in seven countries and six languages, presenting the stories of 100 Korean women and men, born from 1944 to 1995. Eighty-eight were adopted abroad and now live around the world. Twelve aged out of their orphanages, and mostly live in Korea. To my knowledge, this is the most expansive collection of Korean or inter-country adult adoptee narratives in existence.

Each interviewee, in one sitting, tells their story—from their earliest information and/or memories from Korea, to their adoption and upbringing in their adoptive families and countries, to their journey into adulthood, and up to the filming. We quickly begin to understand the unimaginable disparity of our subjects, contrasting the stories of the nurtured and the abused, the blessed and the broken, the loved and the lost, and the stories that lie between. Each session is its own film experience, captured as subjects drew on repressed memories, connected events, finally acknowledged truths, resolution, and reconciliation. All interviews can be watched online.

Adult adoptee voices have only just begun to be heard.

Through personal memoirs, literary fiction, and scholarly works, articles and blog posts, art and film, adult adoptees are now going far beyond traditionally simplistic and reductive narratives focused on babies, compassion, rescue, and forever families. We’re getting to the real-life issues that only adult adoptees can speak to with resonance and clarity.

So first and foremost, this project is by adult adoptees, for adult adoptees. Hearing others’ stories can be deeply affirming. It can help you think about and articulate your own experiences and feelings. Many adoptees have long been challenged by painful issues of loss, rejection or abandonment, upbringing, identity formation and racialization, search and birth family, relationships, etc. That’s why there’s such a thriving global sub-culture of adult adoptees, and certainly among inter-country and Korean adoptees. And why thousands more connect to this community every year.

Are adoptive parents listening to adult adoptee voices?

Honestly, the answer is unclear to me. In conferences and heritage camps, film screenings and dinner conversations, adoptive parents frequently express interest in hearing perspectives from adult adoptees. But we heard something different in the “Side by Side” stories.

So if you believe you know your adult child’s mind, I would examine that belief more critically. Virtually all interviewees told us their parents knew little of what they were telling us—including those who characterized their parental relationships as very close and loving. If you think that your relationship is the rare exception, you may be kidding yourself. If you simply don’t want to know what they might really think, then I don’t know what to say. But this project is a way for you to gain real insight into the adoptee experience. It might be painful. It might be very close to home. But you should know that the feelings expressed weren’t in black and white, and there was very little finger-pointing. Painful feelings and hurt associated with their adoption doesn’t mean they don’t love you or wish they hadn’t been adopted. These kinds of complex issues affect all real people and real families. Why would adult adoptees be any less complex?

There were a number of prevalent themes related to adult relationships in adoptive and birth families. Most spoke of a positive and even close relationship with their adoptive parents and families. Even so, while most interviewees had taken some action to find out more about their origins, from looking at their adoption files, up to and including searching for and reunion with birth family, some or all of these actions were kept secret from their adoptive parents. Some were worried that even expressing a desire to visit Korea might be taken negatively by adoptive parents and that searching would likely be offensive and hurtful. On the other end of the spectrum, there were some instances of adoptive parents proactively encouraging an interest in Korea, and in search. But even in these cases, many adoptees continued to be reticent in talking about it with them, especially in relating reunion experiences.

Most interviewees were reluctant to discuss race with their adoptive parents. This feeling started as kids, with a first attempt to discuss racial experiences gone awry, and continues today. It seems most often rooted in the parents’ dismissal of racial experiences as unimportant or something to be ignored. “Color-blindness” or “We don’t think of you as Korean” is taken as a denial of race. Refusal to discuss or acknowledge race results in a sense of shame. Attempts to discuss race by the adult adoptee might have been rebuffed by the parent, as offensive or disrespectful.

Some interviewees expressed a feeling that they were “trophy kids,” and that as adults, parental interest had waned. Others talked about their adoptive parents always seeing them as the child they had rescued, with a heavy and permanent burden of gratitude placed on them, even as adults.

Older adult adoptees are facing the mortality of their parents, and this weighs heavily on them. Being “re-orphaned” was expressed as a concern by adoptees with one or both parents deceased.

Issues related to adult relationships with birth family were tied primarily to the discovery of negative information, which could include any information at odds with a reluctant, loving, and safe relinquishment by an idealized birth mother or family of origin, and a loving selection by their adoptive parents. Discovery of messy and/or conflictive details often led to distancing from the relationship (made easier by literal distance), or outright bad feelings and the adoptee’s unwillingness to proceed any further.

I want to point out that “Side by Side” is not scientific research. My “bullet point” observations in this post are not comprehensive, and they lack context—only the “Side by Side” storytellers themselves make these points as nuanced as they should be. Nor are these observations “data points” from a scientific survey, projectable to the full inter-country adoptee universe. The purpose of “Side by Side” is only to open an intensely experiential window of oral history, of social and academic understanding, and of empathy through art.

Will adult adoptee voices impact the adoption ecosystem?

I hope so. For a long time now, I think that adult adoptee voices have been categorized as “happy” or “angry.” Happy adoptees were pro-adoption. Angry adoptees were anti-adoption. And adoption, as a practice and institution, was sacred and above criticism, for fear of jeopardizing future adoptions.

Today’s proliferation of adult adoptee voices will change all of that. We will hear from all perspectives. We will hear about all outcomes. We will inspect this widely practiced convention deeply and without restraint. We will acquaint society with adult adoptees who are (in turn) happy, angry, sad, grateful, frustrated, optimistic, hurt and, most of all, unresolved. We will show the world, powerfully, that it takes many stories to fully understand adoption and, certainly, intercountry and transracial adoption.